Reflections on AI

Eight Things to Know about Large Language Models

Apr 12, 2023 Source

Here are the eight things (in my own words, to check my understanding):

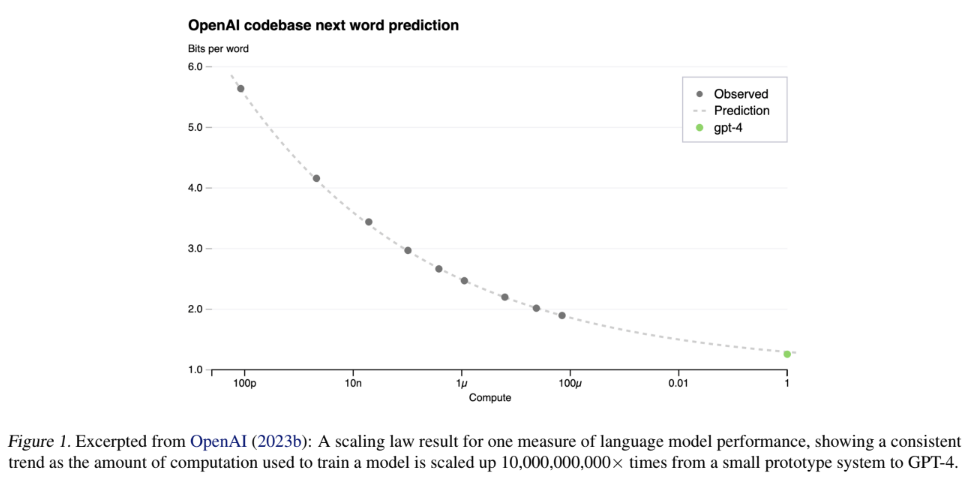

1. Performance of LLMs improves very predictably with increased resources

Here “resources” refers to amount of data, number of parameters, and computational power brought to bear. I am not sure exactly what “parameters” refers to here—something for me to learn.

What is the graph actually telling me? I take it the y-axis “Bits per word” is some inverse measure of performance, but I don’t know what “Bits per word” means, or for that matter what the unit is for the “Compute” dimension (x-axis). Just as importantly: I would like to understand if this is close to an “objective” measure of performance (i.e. everybody agrees it’s a good, useful metric) vs. a subjective way of quantifying it that may be hotly debated among the research community.

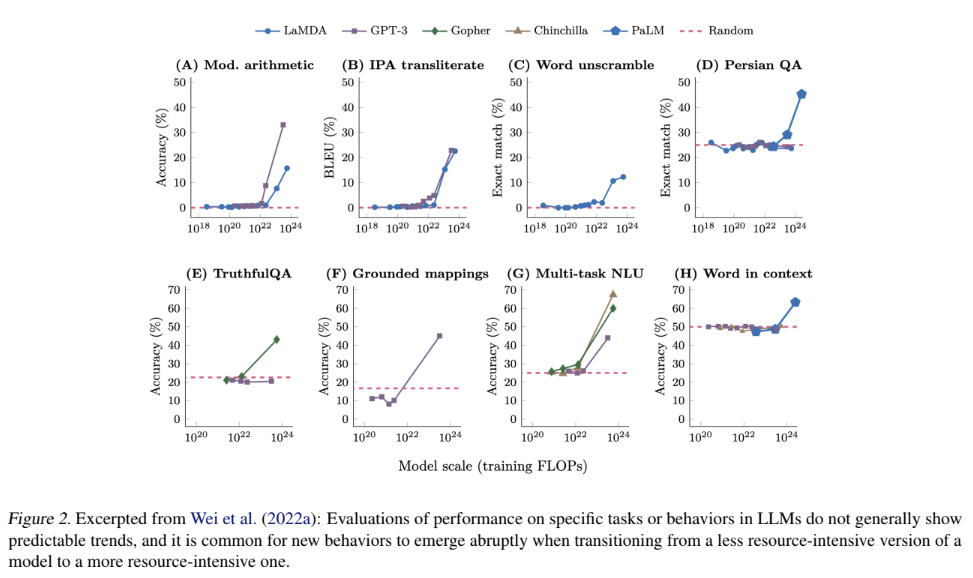

2. New abilities get unlocked as LLMs get more powerful, and we don’t know why

These graphs are really eye-opening.

Often, a model can fail at some task consistently, but a new model trained in the same way at five or ten times the scale will do well at that task.

There are tasks that LLMs simply can’t do, with no signs of progress despite increased investment; and then there is a point of inflection and all of a sudden they can do the task.

I tweeted this here: it’s like how a child develops! A lot of parents with children over 3 years old can relate to this: it’s very common to see your kid “turn a corner” and suddenly be able to walk, talk, draw, understand new concepts, etc. in a very short span of time.

3. LLMs seem to create internal models of the world

Here’s a particularly interesting excerpt from this section:

Models can make inferences about what the author of a document knows or believes and use these inferences to predict how the document will be continued.

Basically, those dismissive voices claiming LLMs are “just predicting the next word” have, in my opinion, failed to acknowledge the emergence of real cognitive capabilities that go beyond this, even if word-prediction is in some sense the foundation of those capabilities. (Side note: it really has me wondering how much of what our own brains do might fundamentally stem from similarly simple primitives.)

To be honest, this already seemed fairly evident to me purely based on the demonstrable capabilities of text-to-image tools like DALL-E 2 and Midjourney. Either these things have internal models, or else I question the coherence of claiming that WE have internal models.

4. We are bad at controlling how LLMs behave

I feel this is related to the 2nd point above about new abilities getting unlocked without us knowing why. A particularly concerning phenomenon covered in the paper is the fact that sometimes the developers of a model don’t even realize it has a certain ability, until they’ve shared it with the public and someone is able to unlock it. For example, OpenAI did not seem to be aware that GPT-3 was capable of “chain-of-thought” reasoning until months after making it publicly available.

Another couple of worrisome trends noted in this section are the tendancy for LLMs to exhibit “sycophancy” (optimizing responses to make the user feel good rather than provide factual information) and “sandbagging” (basically noticing if you seem uneducated and being more likely to feed you widely-believed misinformation if so).

To editorialize for a moment: as a software engineer by trade, I can tell you that this is not even remotely surprising. LLMs seem to me to be the epitome of “emergent architecture”, which is what normally happens by accident when no one is responsible for overseeing the overall design of a system. A classic feature of such architectures is that they are teeming with unintended side effects, which makes it difficult to predict the impact of changes to the system.

5. We can’t explain why LLMs do the things they do

When an LLM gives a response to a prompt, our ability to explain precisely why it gave that response is extremely limited.

This comes back to emergent architecture and the fact that next-word prediction falls far short of a satisfying explanation of what LLMs are actually doing.

My own 2 cents here is that I would argue it’s the same for human brains. We may have a basic understanding of electrical signals traversing networks of neurons as well as a high-level map of which parts of the brain are broadly responsible for which types of mental work; but (at the risk of exposing my ignorance in the field of neuroscience) that seems to be roughly the extent of what we know.

Or more simply: when a human makes a decision, it isn’t like we can explain in great detail what exact mechanistic processes led to that decision. We accept some level of mystery with human beings. The way things are going, it seems to me we are very likely on a path to accepting a similar level of mystery with AI systems.

6. LLMs can get better than humans even though they only learn from humans

There is a very naive perception that I’ve noticed (that I suspect the author has also noticed), that since LLMs are just learning from text written by humans, it follows that human abilities represent an upper limit to what LLMs will be able to do.

There are clear problems with this view, e.g. it does not take into account the orders-of-magntiude difference in scale of input that LLMs can process relative to a human being.

The paper links to some external sources apparently providing examples of LLMs outperforming humans at certain tasks. I haven’t yet read these sources, but they’re going on my reading list!

7. LLMs do not automatically inherit the values of the producers of text

I feel like at this point we’re getting into variations on the same points that have already been made. This one feels like a combination of points 2, 3, 4, and 5.

Having values is arguably just a special case of having an internal model. LLMs develop internal models but we don’t know exactly when or how. And we can’t directly observe the models or predict the behaviors they will drive, let alone control them.

8. It is easy to misunderstand or underestimate what an LLM can do after brief use

This is yet again related to the 2nd point, that LLMs have abilities that seem to get suddenly unlocked given the right input.

The point is that if you just play around with, say, ChatGPT for 5-10 minutes, you might walk away thinking you have a clear sense of what it can and can’t do. But someone else who spends more time with the same system may discover ways of prompting it that result in far more advanced behavior.

Honestly, I think humans are like this too. I.e. someone can hear the same information 10 times and not really get it. Then on the 11th time, suddenly it “clicks”. This has always been a bit mysterious to me. My way of making sense of it is that the brain is a very sophisticated system, and while it can robustly handle a wide variety of scenarios, sometimes an idea or situation is just novel enough that there is a very specific way it must be presented for the brain to absorb it. This could be a function of the presentation itself, or of the environment, or of the state of the brain at the moment of exposure. Most likely, it’s some combination of all three factors (and maybe others).

Possibly the most interesting part of reading this paper, for me, was my increasing feeling as I read it that LLMs might be a lot closer to human brains than most people writing about AI today recognize. Or perhaps it isn’t that LLMs are particularly similar to human brains, but rather that they are converging towards some universal phenomenon of “mind”, which can be built in a number of ways, but which always exhibits some of the characteristics described in this paper.